The first three days are fruitless: we spotted one of these undulating beds, forced to contort within the marl by some tectonic forces. The work, exclusively manual, is too harsh. The cracks in the rock are so tight that the pockets never occur and when the sun reaches its zenith, an unbearable heat stuns us for a part of the afternoon, while the dust carried by upwinds sticks to our eyes and inside our nostrils. We must seek the shade, directly on rock, inside the small holes we dug.

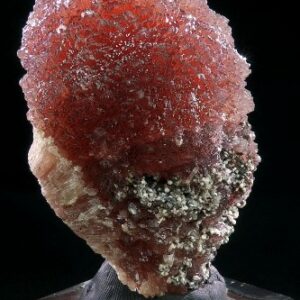

On the third day, during the afternoon, we begin to desperate. Will we ever find a single piece on that windswept rocky protrusion ? Quentin decides then to leave for prospecting a promising but hard to get to bed, nearly at the top of the ravine. On my side, I decide to climb along the current, ungrateful bed to check whether it does not host any mineralization clue before to leave it forever. A dozen of meters further away, a small scree slope catches my eye: screes and landslides are really not scarce in these ravines subjected to intense erosion, that transforms the landscape almost every year. Though, a rusty orange slab attracts me. I approach to pick it up. Finally, it does not look that interesting. Before throwing it away in the nearby gully, I flip it and my eyes open widely: the back side is dotted with lustrous brown-black sphalerites, laying on orange granular ankerite. This will be one of the most significant specimen of the forthcoming find.

I cautiously place the piece in equilibrium on the slope made slippery by the dust and go back up, towards the nearby gully to call Quentin. I see him away, carefully getting down from the upper bed, which forms a thin bar that protrudes from the marls. It looks just thick enough to withstand the weight of a man. I make signs to him. Shouting is useless, cries are blown away by the wind and absorbed by the marly walls. We eventually catch up with each other, smiling. He found several promising cracks as well, filled with faden quartz. Though, this time, the zinc sulphides, so rare in this area, focus our attention. Together, we scavenge the small scree, frantically examining each slab, each black limestone sliver: the hunt for in situ mineralized cracks starts. The fatigue and frustration from the previous days are replaced by the eagerness for discovery.

Above the scree, a slope discontinuity filled by some muddy flows allows the dirty bed faces to appear. We thoroughly scrutinize it, but the dark crystals seem to trick us, caulked behind their dusty coat. We do not see anything. Perhaps is there nothing there, did the blocks felt down from the higher beds ? Suddenly, a tiny white calcite rhombohedron break through the marl accumulated in a rock crevice. And, several centimeters atop of it, a reddish sphalerite stuck in massive calcite come along. Here we are !

We play our tools to move the blocks and reach the fresh pockets, behind. In this area, they are quite different from the typical alpine ones: they are almost never « mature » so the cristals are generally still fixed to the block walls, which can hit two meters long and weigh several tons. The tinkling of the chisels and sledgehammers now reverberate around us, while we separate the pieces from their rock base. We are so focused we do not notice the declining sun’s path, down to its nocturnal hiding place, somewhere at the back of the Ubaye summits. The evening freshness reminds us to wrap the pieces that we then load inside our backpacks. We finally get down, trying to adjust our balance to this new burden: a single and mere fall could damage our valuable cargo and spoil our daylong effort. Staggering, but satisfied at the foot of the ravine, we already think of the following day crystals…

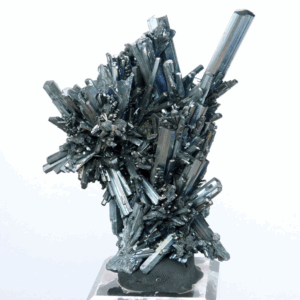

The following days are spent extending the worksite to the limits of the mineralized zone, actually quite narrow. The pockets are tight, but rich in sphalerite, often stuck inside the granular ankerite. White calcite and very thin faden quartz are combined with the metallic crystals, whereas an ochre oxide painting stains the limestone gangue. Sometimes, some small platy gypsum coats the oxides.

At night, we clean up the pieces, that end up filling any available space on the balcony of our accomodation. Around 200 specimens were extracted during these 4 days long work, among which a dozen of them are exceptional in our opinion, for their quality, architecture or crystallography. The sphalerites color varies from brown-reddish to green-yellow, with sometimes even color zoned crystals. Some of them are even genuine ‘cleiophanes’.

The pictures below capture the natural beauty of some of the best specimens from that surprising find in the Southern Alps.